If your goal is to expand your music taste, an obvious suggestion is to listen to new music. While this is important, it’s not enough and in this post I discuss the extra steps needed to turn music exploration into a transformational process. These steps help you stay open and curious as you encounter new songs. By fostering receptivity, they help you overcome the primary hurdle as a listener: the biases that come between you and the song.

The Problem of Mishearing

Whenever we hear a song, we hear it as something. We always bring a “frame” or context to bear on what we’re listening to, and this shapes our experience of what we’re hearing.

For example, we may hear a song in terms of the artist: experiencing it as “a Moneybagg Yo song.”

Or we may hear it in terms of genre: experiencing it as an instance of “Memphis rap.”

Or we may hear it in terms of a frame of reference that has little to do the song itself and is more about our aversion to music of this kind: experiencing it as an instance of “the dreadful state of popular music—no melody, no harmony, just talking over a drum machine.”

This last example is what I mean by the term “mishearing.” It is not anchored in careful attention to the song itself. Instead, it imposes an alien frame of reference on the song that obscures whatever special qualities it has to offer. The listener blames the song for not being what the listener thinks a song “should be.” What is actually there to be heard and appreciated ends up being missed entirely. And this is because the listening frame being brought to bear on the song is inadequate to the song.

I love intricate melody and harmony. Brian Wilson is a musical idol of mine. But blaming a hip-hop tune for being deficient in these qualities is like criticizing Pet Sounds for its lack of hard-hitting beats.

This is probably obvious, but the reason I bring it up is because I see this kind of “mishearing” as a major obstacle to connecting more deeply with music and expanding one’s taste.

My Own Mishearing

At least this has been my experience. For decades I was estranged from contemporary music because it all seemed deficient to me. Shoddy playing, simplistic melodies, boring chords. It seemed like music had been in a freefall over the past few decades, and had reached the point of being nearly unlistenable.

I read articles online suggesting that even new generations of listeners were ignoring new music and gravitating towards the songs of the past. This only reinforced my position. It became the default mindset I brought to bear on most of the new “popular” music I came across. I was looking for what wasn’t there, (e.g., things like key changes, bridges, multipart harmonies, etc.), and not surprisingly, I found the music nearly impossible to enjoy.

What I was doing was listening to current music in terms of a context that formed decades ago and was flash-frozen in early adulthood. I knew I was doing this—I’d read research about the relative inflexibility of musical taste as one ages and was aware of advice to continue to expose myself to new music in order to break out of this. But here was my problem: what’s the motivation to expose yourself to new music when it all sounds terrible to you? Do I just strap my headphones on and grit my teeth?

I came to realize there was something missing in this advice: it’s not just about exposing yourself to new music. That is important, but you need to go beyond that and do at least four other things:

Steps to Expand Your Music Taste

1. Adopt Beginner’s Mind

To overcome mishearing, you need to actively bracket out your existing frameworks for evaluating music. At least for the duration of time you’re exploring new stuff.

Is there something you won’t listen to because it’s too cheesy or commercial? Or maybe because it’s too hip and trendy? Have you been turned against certain genres or artists by music critics and online tastemakers? I’ve found it essential to suspend these pre-understandings of what “good music” is in order to discover good-music-for-me.

Another trap can be getting too attached to one’s own existing preferences. The downside of knowing what you like is that you start noticing its absence. I used to skip songs immediately if the chords were boring; for years this blocked me from discovering aspects of rhythm and sound-design that really speak to me in modern music. I needed to bracket the “chords preoccupation” in order to discover new dimensions of music that I resonated with. A stance like what the Buddhists call “Beginner’s Mind” is helpful here.

2. Expose Yourself to New Music

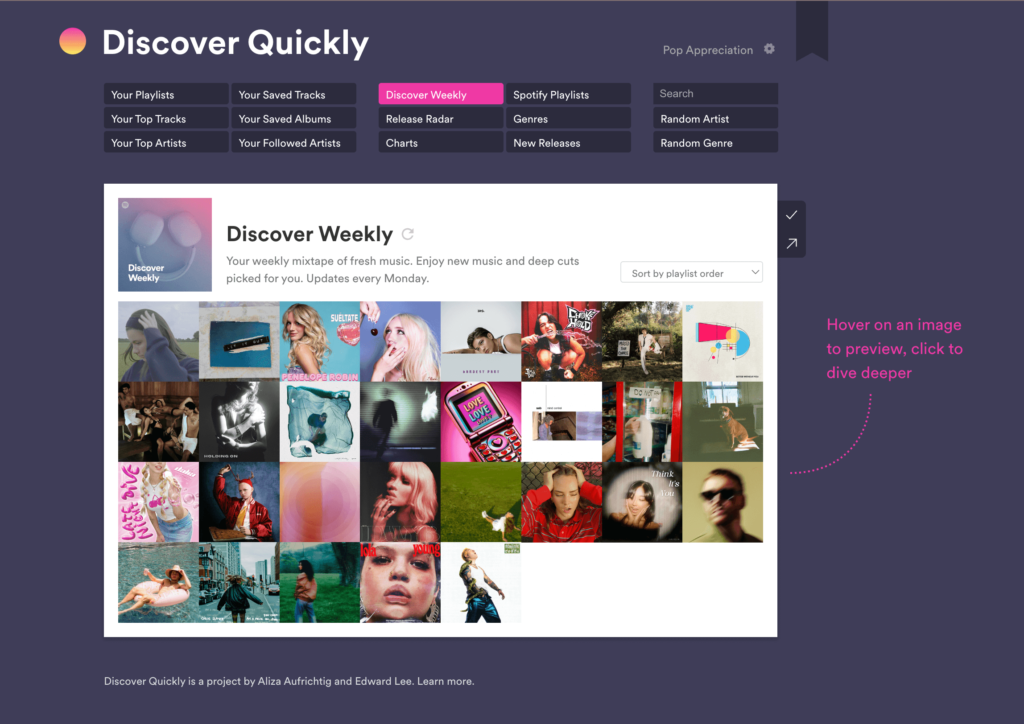

Now this step is of course important. To expand your taste, you’ve got to be feeding yourself new music. Here’s a tool that helps you do this easily: Discover Quickly.

You can choose from hundreds (thousands?) of music genres and rapidly sort songs by a variety of parameters like tempo, popularity, and newness. To hear a song, just mouse over the album cover for a 30-second snippet. You can blitz through a genre in minutes, getting a sense of what draws you and what does not. This allows you cover a lot of ground quickly, and rapidly generate leads to follow for more in-depth exploration.

There are other nuances to this tool that are worth exploring. For example, say you found a song that pulls you. Or an artist. You can click “recommended songs based on this” and get a whole new list of songs to sort through like the one you’ve picked. I’ve found a bunch of new songs by repeating this process over and over, diving deep into unfamiliar parts of the musical landscape.

And if you’re a Spotify user, exporting the songs you’ve found to a playlist is as simple as clicking a button.

3. Listen-to-Discover

A given activity, (like listening), can vary tremendously depending on the intention with which it is done.

For example, if you’re saying something important, and someone else is listening to you, it will feel very different if they are “listening-to-speak” rather than “listening-to-understand.” On a physical level the activity is the same: the person is looking at you, they’re nodding and smiling, but on a qualitative level it feels very different. So different, that it can be hard to even talk when you sense the other is listening-to-speak.

Transposing this from the realm of conversation into music: there’s a big difference between “listening-to-evaluate” and “listening-to-discover.” And this mindset shift makes all the difference when exploring new music. If you find yourself stuck in a rut despite exposing yourself to lots of new music, this may be part of the problem.

What’s the difference between these two modes of listening? Listening-to-evaluate involves asking the question “do I like this?” as you take in the song. This mode emphasizes the “I” and is therefore a more self-focused form of listening. It engages the conscious mind in making an appraisal, which it does based on the storehouse of knowledge you have about what you like (e.g., “I like fast songs, and this is slow, so I’m moving on”). This tends to lock you into the familiar and undermine efforts to expand your taste.

Listening-to-discover involves asking the question “what is here for me to notice?” It shifts attention from you to the song and is a more “other-focused” form of listening. When you come across a song you like, it will strike you—almost seize you—if you’re in this state, but you’re not consciously trying to make an evaluation while listening. You’re not looking to confirm the presence or absence of something you already know you like. You’re trying to hear more in what is there and allowing any feelings of affinity to arise naturally if they’re going to come at all.

When listening with this discovery mindset, you’re not just “exposing yourself to new music,” you are “exposing yourself to new music in order to discover what draws you.” There’s a subtle, but important shift in intention here. You’re not just “hearing new stuff,” you are “engaging in a self-discovery process.”

Framed this way, there’s a purpose to the listening that endows it with a whole different feeling quality. It makes the listening process more like true exploration. And it makes you more attentive to novelty and difference as you listen, which are necessary elements for evolving one’s taste.

When I was in Tae Kwon Do as a kid I was taught to “kick through the board” in order to break it with my foot. If I aimed at the board itself, I wouldn’t succeed. Same with new music exploration. You are not just listening to new songs, you are listening to new songs in order to elaborate your own preferences. The “in order to” is important; you are aiming for something that goes beyond the physical activity of merely taking in sound waves. You are making discoveries both about yourself and about music at the same time. There’s the potential to uncover something new with each song you play. Holding this in mind while listening will re-enchant the music exploration process and help you transcend listening habits that keep you stuck in the familiar.

4. Pay Attention to Pulls

When sifting through new music, it’s important to notice when some part of you is drawn to what you’re hearing, even if your conscious mind objects. I call this a “pull.”

Practice noticing the subtle flickers of interest that show up with certain new songs. I’ve found that they can be easy to overlook, especially when it comes to fledgling musical preferences that I’ve yet to become fully aware of.

If you’re like me, there may be entire dimensions of music, like rhythm or timbre, that you’re not paying much conscious attention to right now. There may be preferences, waiting to be birthed, in those dimensions for you. Because you’re not used to listening for it, your conscious mind will likely overlook it, but your subconscious won’t.

Experientially, it’s like something in the song snags your attention, but you’re not sure what. These pulls often show up as a whole-body response of some kind. A lingering on the song. A sudden swaying of the body as you listen. An urge to turn up the volume just a little a bit.

In my experience, these “new shoots” of musical interest require sustained attention to develop into full-fledged preferences. This is why I put songs that pull me into a single “pulls” playlist for future exploration. I keep coming back to them, over and over, and I gradually discover what is beckoning me.

5. Create Your Own Categories

The final step is to allow new frameworks for appreciating music to organically emerge as you bring careful, curious attention to whatever is drawing you.

As you come back to these songs repeatedly, patterns start to become apparent. You begin getting a sense of the quality that is drawing you in a particular cluster of songs. If you can find a label or image for the pattern (I call this a “handle” borrowing the term from psychologist Eugene Gendlin), it foregrounds and fixes the subtle quality in awareness, making it easier to return to.

You begin to develop language for that which is pulling you. You learn to recognize it. You are discovering what you like by allowing your conscious mind to be educated by your unconscious mind, which speaks in the language of feeling, imagery and movement1.

This process leads to the development of “personal microgenres” which are the figures or motifs that you, as a particular listener, have a special affinity for in music (here is an example of one of mine, and here’s another). This is a delightful thing to discover. Consider this: there are qualities that you have a gift for noticing and savoring in music—things that speak to you in a way they may not to others, and which bring you bliss—and they are waiting for you to uncover them. They may go undiscovered if you don’t embark on the adventure of seeking them out.

This step personalizes your experience of music. You begin listening in terms of frameworks you generate rather than relying on the conventional ones provided by the culture (which may or may not help you connect with the pleasures particular to you as a listener).

In short, to expand your music taste you need to grow new, personalized, categories for making sense of music. You need to develop your own contexts for appreciation. Contexts adequate to the music you’re listening to, because they grow out of loving, sustained attention to it. This is what expressive playlisting does.

Here’s the good news: the tools are available to do this now. The tools to listen in this way did not exist in decades past. Expressive playlisting capitalizes on the streaming music model and online resources like Discover Quickly. The ability to zip through thousands of songs and use thin-slicing to detect pulls that invite deeper exploration, would not have been possible in 1990. An entirely new way of exploring music has developed over the past decade and a half, and despite its drawbacks it makes it easier than ever to rapidly evolve one’s taste.

The Importance of Receptivity in Expanding Your Music Taste

I want to wrap this post up by making a comparison to psychotherapy.

Exposure therapy is the gold-standard treatment for phobias. For exposure to be transformative, how you do it is critical. If you do it in a non-receptive way (e.g., “white-knuckling it” through a spider exposure), it ends up being less effective than if done from a stance of openness and curiosity. This is because you take in less information when you’re closed off and the potential for new learning is reduced. When it comes to exposure, the quality with which the activity is done matters.

The same applies when trying to expand your music taste. It’s not enough to expose yourself to new stuff—there are important “inner” shifts one needs to make in order to be optimally receptive. These include: 1) suspending pre-existing listening biases, 2) adopting a discovery mindset by “listening-to-discover”, 3) noticing when something novel piques your interest and 4) allowing nascent preferences to emerge through sustained attention on what seems to be drawing you. With these extra steps, exposure to new music can extend and elaborate your preferences so that more of music becomes available to you for enjoyment. You gradually expand your taste in a way that is authentic, organic and deeply rewarding.

Notes

- Or in the framework of Iain McGilchrist: your left-hemisphere acts on what it’s provided by the right hemisphere, making an implicit, intuitively grasped preference into something explicit, and enriching it in the process. For more on this, see his book The Master and His Emissary. ↩︎

Last Updated on May 16, 2025